Home » INW Research grows alongside neurology clinic

INW Research grows alongside neurology clinic

Company plans to delve into investigator-initiated programs this year

February 27, 2020

After years of frustration as bureaucracy impeded research efforts, Spokane-based neurologist Dr. Jason Aldred decided in 2018 to launch his own research center dedicated to finding solutions to neurological disorders.

Since then, Inland Northwest Research LLC has participated in dozens of national and global clinical studies, Aldred says.

Jill Ciccarello, CEO and research program director, says Inland Northwest Research currently is running 21 clinical trials for drugs, devices, and treatments aimed at treating Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, and ALS. The company is currently enrolling in 11 trials, and expects to start six more this year, she adds.

Clinical trials work on a rolling basis, so some of the 21 trials are wrapping up, she says.

Of those 21, Dr. Steven Pugh, a principal investigator with the company, says four of the trials are focused on multiple sclerosis and dementia. One such study, dubbed Verismo, is exploring the effects of Ocrelizumab on patients with multiple sclerosis and the risk of developing breast cancer and all malignancies.

He adds that he expects to start a fifth study this year on multiple sclerosis.

Pugh, a neurologist specializing in multiple sclerosis, co-founded Selkirk Neurology PLLC, a medical clinic specializing in neurological disorders, with Aldred around the same time Inland Northwest Research was founded. Pugh has no ownership stake in the research company.

Both Pugh and Aldred decline to disclose specific details about the studies, citing nondisclosure agreements. However, Aldred says the team is currently working on a study to sequence the known Parkinson’s genes for hotspots and abnormalities.

The studies are funded by sponsors — medical device makers or pharmaceutical companies, typically — or through grants.

Aldred adds that Inland Northwest Research worked for two years to be approved to work on projects for Huntington’s Disease, as trials are limited, and companies must go through a rigorous screening process to participate.

On average, each clinical trial performed by Inland Northwest Research enrolls between six and eight patients.

Pugh says most of the diseases the company is studying don’t have FDA-approved treatments.

“We’re trying to find things that slow those diseases down because right now, what we do is we treat them symptomatically,” he says.

He adds that MS is the exception, as several treatments have been approved that alter the course of the disease.

“I think there’s an expectation when patients come in that somehow we’re going to cure them, we’re going to reverse the clock, (but with) a lot of these neurodegenerative diseases, there’s no treatments that have been approved that even slow them down,” Pugh says.

Owning a private research company has several advantages, Aldred contends.

“(I) decided to come out to Spokane because the business environment here for practicing medicine is similar to other parts of the country, but it’s still more permissive to entrepreneurial business models, particularly in medicine,” Aldred says, adding, “I came here to have an independent medical practice and also to have independence to dictate how our research program would go.”

The model allows for Inland Northwest Research, which specializes in national and global research for neurological disorders, to bypass some levels of bureaucratic oversight faced by academic institutions and hospitals, enabling the company to negotiate and finalize business contracts quickly.

Ciccarello says it usually takes three to five business days for her to turn around a contract and budget — while it traditionally has taken larger companies at least six months to confirm a contract.

Pugh says, “If you’re being held up for six months to a year, the study could potentially be closed by the time you get around to it.”

Aldred adds that typically by the time Inland Northwest Research starts a study, recruits patients, and completes a study, other centers are getting the green light.

The company also has a centralized institutional review board, which simplifies the review process, he says.

A centralized review board is used in multicenter studies and conducts reviews on behalf of all study sites that agree to participate.

Aldred says having Selkirk Neurology next door is a benefit as well, as the patients who receive clinical care at Selkirk and have an interest in participating in research have more opportunities to do so with the easy access to the research clinic.

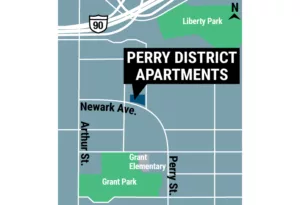

Selkirk Neurology occupies about 5,000 square feet of space just down the hall from Inland Northwest Research at 610 S. Sherman, in Spokane. Aldred adds that patients who participate in clinical trials aren’t required to be patients at Selkirk.

He adds while Selkirk Neurology and Inland Northwest Research complement one another, they are two entirely self-sufficient organizations.

“They’re different, but kind of this seamless option for patients,” he says. “The clinic benefits from having the research center, and the research center certainly benefits from having the medical clinic, but they’re self-sufficient in and of themselves.”

Inland Northwest Research employs seven, while Selkirk has 19 employees.

Ciccarello says Inland Northwest Research receives hundreds of study proposals a year. The research team vets the proposals thoroughly to determine whether they’re ethical, have scientific merit and validity, and address a deficiency before the company takes them on, she says.

“If we wouldn’t put our own parents and neighbors in these research programs, then we wouldn’t take them on here,” Ciccarello asserts.

She adds, “Philosophically, the research supports their mission in their private practice, which is to make health care personal again and to also provide opportunities for their patients and address deficiencies in clinical care.”

As part of that mission, says Pugh, patients who participate in a clinical trial with Inland Northwest Research are educated not only on the parameters of the study they will be involved in and what they can expect, but also any alternatives and what happens if they decide not to participate.

Aldred contends laws in the U.S. regarding clinical trials are lax enough that a company can boast its treatments have more of an impact than it actually does, which he says can be risky and costly for patients.

“We want patients to be sure that they get high-quality, well-supervised research where there’s oversight,” he says.

Inland Northwest Research also places value in educating future neurologists and brings on six medical students from Washington State University and University of Washington a year to do their neurology rotations, during which time the students also are exposed to clinical research, Aldred says.

Aldred says he wants to collaborate in the near future on projects with startups and biomedical development companies in Spokane, as well as develop Inland Northwest Research’s own projects — known as investigator-initiated programs.

As an example, Aldred says he currently is working on a project in telemedicine on deep brain stimulation to make the currently approved treatments more accessible.

“We have this great medical system that not a huge percentage of the population has access to,” he says. “So, how do we attack that problem intellectually and come up with a way to partner with a medical device industry, find patients, and come up with possible solutions to address that in our own environment and community?”

Latest News Health Care Technology

Related Articles

Related Products