Catching up with Shaun Cross, Maddie's Place president and CEO

Nonprofit receives nationwide interest, positions itself as parent organization

_web.webp?t=1770883313&width=791)

Maddie's Place has inspired 41 cohorts in 35 states to form similar facilities, says CEO and President Shaun Cross.

| Karina EliasLast April, Maddie’s Place President and CEO Shaun Cross was worried the Spokane-based neonatal transitional care facility might not secure $2 million from the Washington State Legislature to continue operating.

To help prevent a potential closure, the organization launched a social media campaign. The campaign not only helped raise additional funds but sparked national interest, with groups in more than 30 states now exploring how to bring a Maddie’s Place-style facility to their communities, Cross says.

Maddie's Place ultimately was allocated $2 million from the Legislature, which will help the nonprofit continue operating through summer 2026.

“What really fascinated me was comments from donors saying, 'Please, we need to start a Maddie’s Place in our community,'" Cross says. “We put together six webinars on our site on how to start a Maddie’s Place. … We have 41 cohorts in 35 states that are starting to meet across the country.”

The surge in interest underscores the impact of the opioid epidemic across the country and highlights the successful model of care that Maddie’s Place provides, Cross asserts.

The nonprofit organization has trademarked its name and logo and has licensed its intellectual property as it prepares to help dozens of other communities start facilities, with the Spokane site positioned as the national parent organization. In Washington state, Maddie’s Place has groups in Vancouver and Bellingham working toward launching sites.

“This could be huge for Spokane,” Cross says.

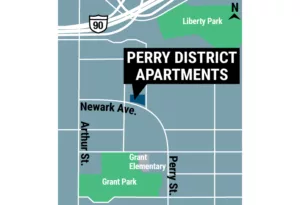

Established in 2022, Maddie’s Place, located at 1004 E. Eighth, was founded to treat infants experiencing withdrawal due to prenatal substance exposure, including opioids and synthetic opioids, known as Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, or NAS.

In 2025, the facility treated 59 infants with NAS, up from 44 infants in 2024, a 34% increase. Since opening, Maddie’s Place has cared for a total of 172 infants, Cross says.

A Washington State University study has found that the state of Washington has double the national rate of NAS-born babies; Spokane County has triple the national rate of NAS-born babies.

Additionally, the organization has refined its mission to treating both babies and parents, known as caring for the “dyad.” The organization has provided services to 170 biological parents, with 100 parents staying onsite with infants and 49 parents staying the full duration, Cross says. Of those 49 parents who stayed the full duration, 88% are now in recovery, housed, and have custody of their children. While the facility does not medically treat the parents, they offer wraparound services and a supportive nonjudgemental environment, he says.

Maddie’s Place is a 24/7 secure facility with 95 employees, including 23 registered nurses, 47 infant care specialists, 10 peer support staff, and administrative personnel.

“The parent in recovery is the best medicine for the infant, and the infant in recovery is the best medicine for the parent,” Cross says. “Their mutual recovery based on the treatment of the dyad right after birth, … that’s where bonding and attachment are most likely to happen.”

Nationwide, there are only five such neonatal transitional facilities, Cross contends. Spokane is one of two facilities that provide this specialized dyadic model of care that treats infants and parents together.

Currently, the health care industry typically operates by separating parents from their newborns, often moving newborns into Neonatal Intensive Care Units in hospitals and weaning them off their addiction with morphine for close to a month, Cross says. But, the first month of a baby’s life is a significant period in which babies and mothers are biologically meant to bond and attach, he asserts. Since these mothers are often unhoused women who are discharged without their babies, they often return to living on the streets or in shelters, he says, adding that their babies often go into foster care.

Neonatal transitional care facilities operate using a patchwork of funding. Maddie’s Place, which provides its services free of charge, has a $4.5 million annual budget; it has raised funds through state and local grants and donations, but lacks consistent and permanent funding, Cross says.

Cross, 75, who has a 35-year career as a lawyer and is a partner and general counsel with Spokane-based Lee & Hayes PLLC, has been working on state legislation that would create a funding model for these treatment centers and lay the groundwork for Maddie’s Place to expand statewide.

Senate Bill 6024, authored by Cross and introduced to the Legislature in January, proposes to direct the Washington State Health Care Authority to create a bundled payment model in which Medicaid funding pays for infants experiencing drug withdrawal, and funding from the Department of Children, Youth, and Families will pay for maternal treatment, says Cross. The bill also proposes to provide bridge funding of $2 million a year while the reimbursement system is built, he adds.

Cross also helped author a federal bill that proposes commissioning a three-year comprehensive study of the prevalence of NAS in all 50 states and of the outcomes of the five clinics across the country, he says. Dubbed The Miracle Act, the bill is intended to push states to adopt reimbursement models.

“The Miracle Act is essentially laying the groundwork for the state to do this to amend their state Medicaid plans,” Cross says. “Because once the states see how bad this is, they’re going to say, we’re better than this as a society.”

Maddie’s Place is also in the midst of expanding its campus. As previously reported by the Journal in October 2024, Maddie’s Place purchased a one-acre property for $1 million that neighbors the organization's existing property.

A master plan is currently underway that envisions a $15 million to $20 million expansion of the current facility to accommodate mothers before they give birth, Cross says.

On the West Side, there are treatment centers that provide withdrawal treatment to pregnant women. However, those women don’t have anywhere to go once their treatment is over. Maddie’s Place will contract with those facilities and provide housing for women at eight months pregnant who have gone through the treatment program, he says.